Despite what critics say, China really does have an advantage in the fourth industrial revolution, and this why.

There has been a spat of articles suggesting China's advantage in AI is overblown. We disagree with their conclusion, as not only does China have an advantage in AI, it also has an enormous advantage in the fourth industrial revolution. Our rationale takes us to The Innovator's Dilemma.

Carl Benedict Frey and Michael Osborne wrote an article, last month, for Foreign Affairs arguing that China does not have a significant advantage in AI. They are both brilliant economists and have written some superb thought leadership on the future of jobs and technology, including Frey's already influential book The Technology Trap.

Despite their impressive track-record, we think that they have underestimated the levels of innovation and experimentation which are truly underway in China. We are going to stick our necks and out and say we think they are wrong in their conclusion.

Let’s start our rationale by discussing The Innovator's Dilemma.

The late Clayton Christensen, a Harvard University professor and businessman, famously penned The innovator's Dilemma in 1997 — a tale about the downfall of market-leading companies caused by technology innovation. Why is it that great and powerful companies fail? The Innovator's Dilemma put it down to these companies missing the next significant shift — a shift that was often technology-led. We think that The Innovator's Dilemma serves as a good model to explain the inevitable rise of China not only in AI but in fourth industrial revolution technologies in general.

Christensen took as an example the disc drive market. He noticed that every time there was a major shift towards a new sized disc drive, for example from 14 inch to eight-inch to 5.25 inch to 3.5-inch drives, most of the market leaders failed and new companies, previously dismissed as unimportant, rose to pre-eminence.

It's important to note that this only happened when there was, and an excuse the use of cliché, a paradigm shift. (we are not fans of the phrase paradigm shift, but this is one of the few occasions when it really is appropriate.)

For as long as the disc drive technology was evolving, jumping from say ferrite-oxide heads to thin-film heads, the market leaders kept their position.

The market leaders who failed to spot these changes had often researched their market extensively, complacent in their current commercial success. The research suggested that the customer was not interested in this 'new-fangled technology, barely better than toys.' Even so, the research was wrong; once the market conditions and underlying technology changed, customers changed their mind and adopted it.

The specifics of how this happened is important and relates specifically to China in the unravelling tale of AI and the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

In the case of the disc drive market, while market leaders dismissed the new technology, some smaller companies didn't. They specialised in this new type of disc drive, and as the market changed, for example, mini-computers gave way to desktop PCs, no one wanted the old eight-inch drives, they wanted 5.25-inch disc drives. The established players tried to change, but it was too late, the new companies that they had previously dismissed now had superior products and specialism that the older companies could not easily match.

The tale of The Innovator's Dilemma has a similarity with a theory in evolution theory know as Punctuated Equilibrium, where an isolated group of a species evolves a new adaption, and then at a future date, if the geography changes, they mix with the original species. The new mutated species often had a superior adaptation and came to dominate. The fossil record then appears to show a very abrupt change in the evolution of that species.

Stories about business are replete with such similar examples — Blockbuster disrupted by Netflix, Apple and new smartphone players disrupting Kodak as well as RIM/Blackberry and Nokia. Tesla is another example of a disruptor, its specialism in AI and battery technology is giving it a significant advantage over other car companies — it's a classic Innovator's Dilemma scenario.

China the Disruptor

We see no reason why the lessons of The Innovator's Dilemma can't apply to nations.

China has been investing in new specialisms while the rest of the world watches on.

A possible factor here is that many of these new technologies require massive upfront investment with a very long pay-off. Established countries are loathed to make investments of this size, because such investments can cannibalise their existing products. Mature countries often have the mindset that new investments require a much higher level of proof of value, making them less resistant to experimentation. China and other developing markets are starting from scratch, so are less encumbered with their technology legacy. The markets are notoriously poor at providing finance with long-term return. That is why many great innovations start with the government, such as the Internet — which began life as Arpanet part of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) of the United States Department of Defence.

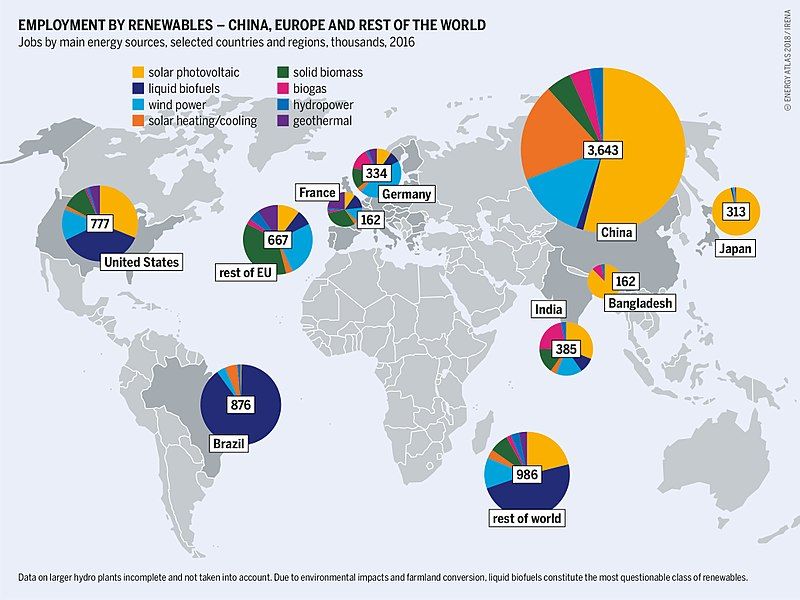

Linked to this is the idea of a learning rate — certain technologies fall in cost and rise in sophistication at an exponential rate as their sales increases. Renewable energy is a good example of learning rates — falling in cost at a rate related to the increasing size of the installed base.

Technological innovation is rarely viable at first. — it goes through a learning rate. The first stage of a technology evolution is proving it and evolving it to be adoptable. The second phase is its fuller adoption, disruption of incumbents and productivity benefits.

The markets are not always good at funding technologies before these benefits have set in, particularly when these require significant capital expenditure.

So that is China's significant initial advantage — massive government investment.

It has many others also which cannot be discounted.

PrivacyThe privacy argument is important, and its implications not widely understood. AI needs data. Once we start using data, we very soon run into arguments about privacy.

In the West, we care about privacy. The tale of Orwell's 1984 has left a deep mark upon the Western psyche. Experiences of World War 2 and the Gestapo, and then experiences in Eastern Europe behind the iron curtain, means that in the West there is a fear of an encroachment to our privacy bordering on paranoia.

Some policy makers have recognised that in the West, consumers are so distrustful of authority and corporations that they will be reluctant to officially give up their data unless they trust that their privacy will be protected. So, they pass regulation to try and create this trust. This is why we have seen a spat of privacy regulations, such as the EU's GDPR and California's CCPA.

In China, privacy is a less sensitive issue.

So, if AI needs data, and in the West, there is a reluctance to officially give up privacy without significant re-assurances, China is at definite an advantage. And this advantage lies with different cultural attitudes. It is an advantage that lies deep.

The resulting greater availability of data in China doesn't just mean more AI; it means more opportunity to enhance speciality in AI algorithms and a greater opportunity to create a workforce that understands AI and create productivity faster.

It's not just that China has more data that gives it an advantage. It is that more data creates activity which in turn creates a workforce with skills that are more appropriate for the 21st Century.

Mathematics

Mathematics is seen as an incredibly important subject in China.In the UK, not being goods at mathematics is almost seen as something to boast about — the cool kids didn't do the subject. How often do you hear people laugh and say, 'I was never good at maths,' only for others to nod in agreement? Who cares anyway? Who needs to know trigonometry or Pythagoras's theorem?

In China, it is not like that. The Mathematics Olympiad is enormously popular. It's cool to be good at algebra or calculus or geometry in China.

And being good as Mathematics is something you need to be if you are going to write algorithms for an AI system, or be a data scientist.

For that reason, China has a massive advantage.

Barriers to entryThe next point is not so much an argument about China; it is one about developing and new frontier markets. New technology is handing these markets further advantages to leapfrog — or at least to reduce the disadvantages that used to hold them back.

Consider the list:

• Lack of clarity in defining property right ownership, as described by Hernando De Soto is one area that has held back emerging markets — distributed ledger technology may provide a fix.

• Access to banks — online banking is solving that.

• Lack of access to education — enter online learning.

• Access to the national grid for electricity — renewables removes the need for such access.

But above all, we would say that digital technologies have lowered barriers to entry. It is now much easier for developing and new frontier countries to compete with the help of digital technologies.

As for China, these low barriers to entry provides it with an opportunity to accelerate closing the gap with the West. Indeed, in some ways, the West, with its legacy systems, is at a disadvantage.

Why this time is different.

An important point is not to compare China today with Japan 30 or so years ago. Back then there was a commonly held view that Japan was inexorably on course to overtake the US.

There are many reasons why this didn't happen. Here are three of them:

Firstly, Japan is a much smaller country than the US. Secondly: demographics, in particular the ageing of the Japanese population. But maybe more important than both these factors was the technology cycle. There was no great industrial revolution afoot during the 1980s. Japan was applying and enhancing established Western technologies to enjoy a period of catchup and significant economic growth.

Compare that with today and China. China’s population is almost four-times larger than the population in the US. Like Japan in the 1980s, it has a demographic problem in the making, but this is still several decades off. But most important of all, we are at the early stages of the fourth industrial revolution — a time of significant opportunity.

For China, unlike Japan a few decades ago, its growth is not just about technology catchup, it's about embracing new revolutionary technology faster than the West.

Of course, in a way for China to rise to the top of the economic and indeed technology league is not new, until a few hundred years ago, it had occupied the top slot for one and half millennia, maybe longer.

Complicated

There is one more point about China — it is complicated. The central government does not have as much power as people outside the country assume. After all, China is a vast country with a massive population. This means that China is not subject to stifling central control, strangling enterprise, in the way people often assume.

Copycat

Other critics say that China copies other nations. Whilst this might be true to an extent, it is increasingly looking less like the case.

In any case, isn't copying the way we learn? I am reminded of how the great Hunter S. Thompson, re-typed the Great Gatsby as a way to learn. Besides, I think originality is an overrated idea, as this great video demonstrates all great ideas build in existing ones.

Real-world

Tencent and Alibaba are no longer pale copies of Amazon, Facebook and Google. They are now working on the cutting edge of technology.

But whether it is in renewables, where China leads the world, a Chinese company working with Tesla to create a battery with a million miles longevity, working with CRISPR/cas9 on DNA editing technology and genome sequencing, in 5G (Huawei) or a Chinese company working with IBM to develop a "synthetic molecule that can kill five deadly types of multidrug-resistant bacteria," or in AI itself, Chinese companies are out on the cutting edge.

So What?

If we dismiss China's role in AI and other fourth industrial revolution technologies, we are asking to be blind-sided and disrupted. We become like an eight-inch disc drive company just as the world moves to 5.25-inch players. If we dismiss AI, we are like executives at Blockbusters dismissing Netflix or Decca Records turning away a four-person band from Liverpool called the Beatles.

Above all, China, in partnership with the other nations, can bring its might to develop technology to win the war against climate change, defeat new viruses, and extend lives through the magic of new technology.

But whether you see China as the enemy or an ally, the conclusion is much the same: belittle China's role in AI and other fourth industrial Revolution technologies as your peril.

Related News

Can social media defeat Russia?

Feb 25, 2022

The economy needs more technology and not higher house prices

Dec 14, 2021

The world just tried going cold turkey

Oct 05, 2021