“Overconsumption got us into this mess,” says Amy Britton, founder of Britton Scotland.

overconsumption may be the problem; if consumers examine the products they buy, their sustainability and think about their longevity, not only will that help net zero, it might help their purses and wallets,

Britton Scotland makes products made from Harris Tweed®, the only cloth in the world with its own Act of Parliament. For Amy, what she considers to be common sense, just happens to intertwine quite nicely with Net Zero. Harris Tweed® and Net Zero was not the initial business model but by doing what she felt was good business, Harris Tweed® sustainability is what she got anyway.

“I pay around £120 for my jeans,” she says. “That may seem quite expensive, but I wear them all the time. If they last one year, it works out at 30p a wear. But they probably last three years, that is 10p a wear.”

Look at it that way, and it makes so-called cheap clothes of the throw away culture seem expensive.

Amy Britton on the ESG Show

That T-shirt might have only cost a few pounds, but what is the cost per wear, the cost to the planet? Who made it?

Britton Scotland was involved with the Net Zero Nation accelerator from the get-go. “Collaboration is key to moving forward, “ she says. For her, a community of like-minded individuals who care passionately about the future of this planet creates something better than the sum of the posts: a community that allows each individual to draw inspiration from others. “It reinforces your way of thinking, and discussion is always important. People say: ‘We have tried this.”

But we start with a puzzle. Harris Tweed® is a handwoven cloth handwoven exclusively by islanders in the Outer Hebrides. Yet, that same cloth is exported abroad, maybe to Asia, where it is turned into finished items and then often sold back to the UK, even on the Outer Hebrides. To Amy, the supply chain felt broken and inefficient. It had nothing to do with moving to net zero; it just didn’t gel right. She says that it was after she joined Net Zero Nation she could quantify what that torturous product route meant for the planet.

The beginning of the journey

“When I was a child, everything was made in this country,” Amy states nostalgically. “Then a shift to imported. As a consumer, you had no idea where it was from or the quality.”

She studied and began her adult life doing interior design and architectural design — but soon moved to designing products.

Amy had bigger ideas. What to her was the absurdity of the way products were made; she began making products her way— initially from dead stock, that is to say, fabric not being used, end-of-the-line material, perhaps with minor flaws that would otherwise go to waste.

But, all the research said customers wanted Harris Tweed®, so she began the next stage in her journey. A journey that today sees Britton Scotland as a company fully immersed with both Harris Tweed® and sustainability.

Today, Britton Scotland defines itself as: “an organisation with the mission to redefine the story of Scottish heritage by integrating it with the principles of sustainability and the circular economy. We are devoted to crafting an innovative, environmentally friendly range of products that respect the legacy of our esteemed Harris Tweed®.”

many products “have obsolescence built in,”

The company makes products (including all kinds of bags, cases, and purses) from its workshop in Scotland, with six in-house staff and two contractors. Amy handles product design, financing, marketing, and the rest of the team focuses on supporting these areas as well as product manufacturing— with Amy’s engagement.

Another important part of the company’s ethos is “our products are quite simple,” she says. “The simple design had several benefits: they are efficient to make, have less carbon impact, can be fixed if needs be and dismantled at the end of their life.

The art of fixing things is an art Amy worries is out of favour. She says many products “have obsolescence built in,” if one part fails or wears out, that is it, the product as a whole is no use. She says, “But you can normally fix things if you have an enquiring mind.” Yet she says too many products these days are overly complicated. “Our focus is to keep things simple, with carefully chosen parts that will last which can also be fixed.”

“Our concept was common sense; Net Zero Nation provided us with the ability to measure.”

Net Zero

But Net Zero, she says, “was not on our radar. We just felt that if the materials are sourced locally, why isn’t the final product made locally?” Net Zero Nation presented a way of thinking that chimed with the Britton Scotland rationale. “We realised that we needed to be on the first cohort — it explained what we are doing and what our main goals are.

“At first, it was an eye-opener. We could suddenly see how we spend carbon and the changes you can make.”

“We have changed to a renewable energy provider — allowing us to save carbon.”

“We also changed how we work — for example, how staff commute into our workshop. “

“Our concept was common sense; Net Zero Nation provided us with the ability to measure.”

“You can’t make change without measuring your actions,” she stated.

This takes us into the thorny areas of scope one, two and three. Scope one relates to the direct carbon footprint of what you do, scope two relates to the carbon footprint of the energy supplied to you — and scope three relates more to your supply chain. “You can measure scope one and two easily,” says Amy, “but scope three is much harder.”

Wherever possible, Britton Scotland sources products locally. But this is not always possible — zips, she laments, are an example; not many organisations make zips, she says.

“Thread is from Germany, as we don’t make thread in this country.”

But what Britton Scotland does try to do is recycle as much as possible.

“Our products are typically small and square to minimise waste. All our parts are recycled from PET bottles. Embracing the circular economy. “

Then there is the second-hand market — especially relevant if products are built to last. “I have seen our products on eBay,” says Amy, who emphasises the importance of giving the products Britton Scotland makes a second life.

Sewing

Then there is another lost art — Amy reckons sewing is a skill that is largely forgotten, “but sewing, weaving or knitting is good for you,” she says. It makes sense, the activity of sewing can let the mind wander, another activity that in the era of smartphones seems to be dying — and at who knows what cost.

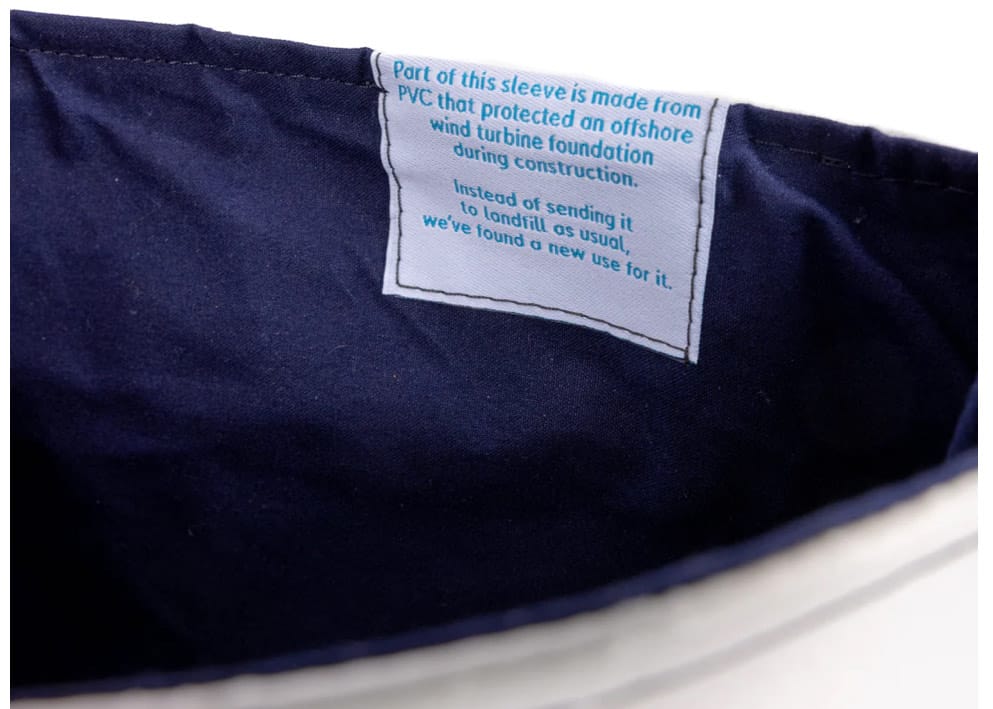

The bag and the wind turbine

One of Britton Scotland’s products is a bag for carrying laptops made from Harris Tweet® and PVC, with the PVC taken from material used to transport air turbine blades used by Orsted.

“PVC is indestructible,” says Amy, “it won’t degrade in a landfill site. We found out about the opportunity from the knowledge transfer network,” but applying PVC wasn’t easy at first. Amy says it took quite a lot of experimenting and then practice before they worked out how to make the product efficiently.

Advice

What advice does Amy have for someone on a net zero journey?

“Start examining your supply chain. But then, if you are in manufacturing, you are probably doing this anyway.

But then, as Amy says, overconsumption may be the problem; if consumers examine the products they buy, their sustainability and think about their longevity, not only will that help net zero, it might help their purses and wallets, regardless of whether they are made from Harris Tweed forming sustainable products from the Britton Scotland workshop.

For more articles in this series, see:

Related News

Introducing The ESG Show Summit

Mar 05, 2025

Is AI really the solution?

Oct 25, 2024

ESG and the CEO

Jul 30, 2024